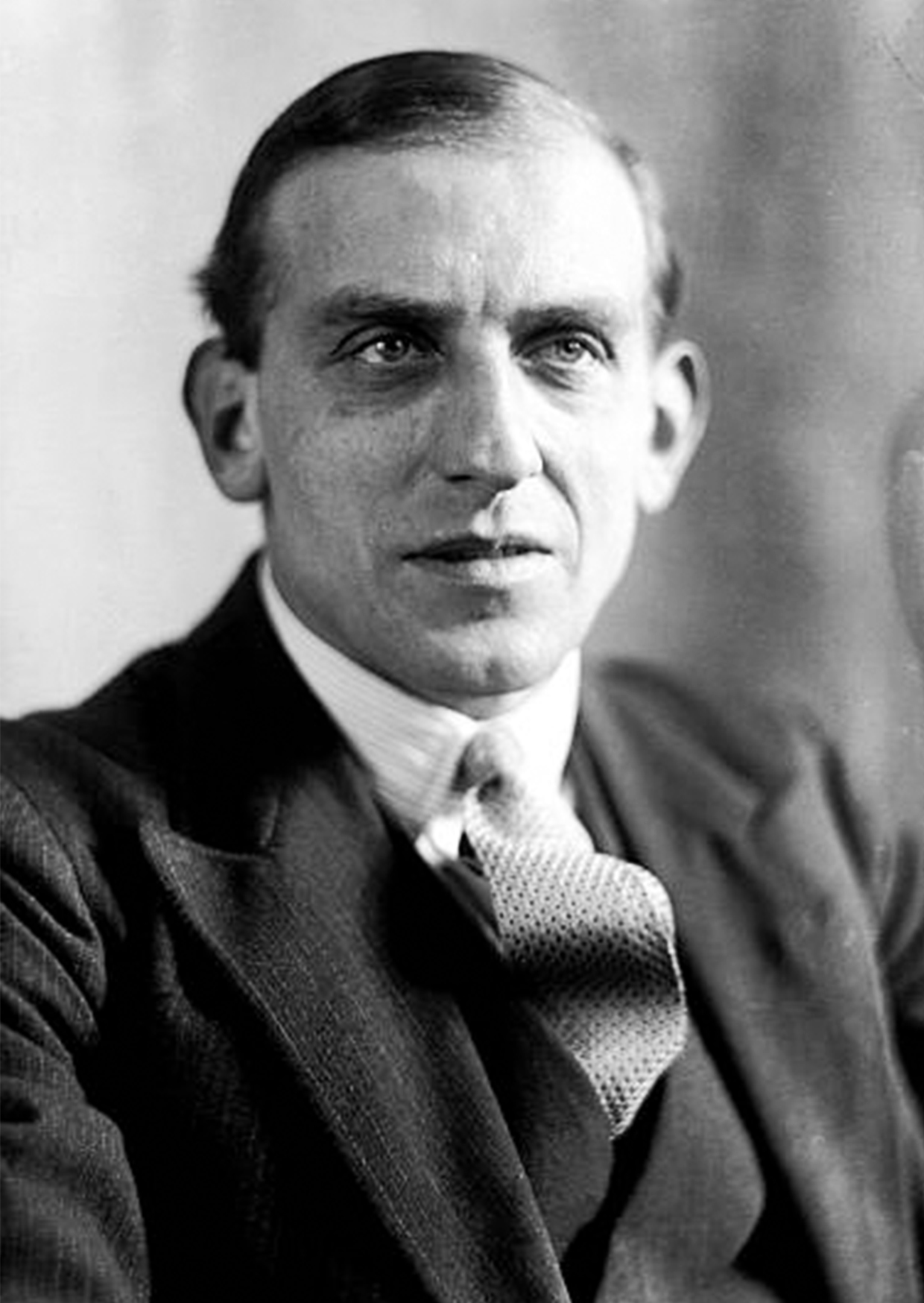

1899

Born on December 5th in Bedford. His mother was from a Welsh Jewish family and his father was a Lithuanian Jewish immigrant.

around 1914

He moved to London and, after a brief stint at St Paul’s, attended Repton School. In 1918, he won the Repton long jump championship.

1918

He served as a lieutenant in the British Army at the end of the First World War, but in 1919 he continued his sporting success at Cambridge, where he studied Law. He won eight times in the 100 and 200 metres flat and long jump at the 1920-23 Oxford-Cambridge races.

1924

At the Paris Olympics, he won a silver medal in the 4×100 metres relay and finished sixth in the 200m. He won the 100m gold medal, the first time in Olympic history that a European sprinter has done so.

1925

He broke his leg in a long jump competition and was forced to give up active sport.

1926

He returned to his civil profession and practised as a solicitor at the Inner Temple until the 1940s.

1978

He died on January 14th at Chase Farm Hospital in Enfield. His funeral was one of the closing scenes of the film Chariots of Fire. The famous footage of young British men in white running on the beach at the opening ceremony of the London 2012 Olympics also evoked his memory.

He held sports-related occupations

He broke his leg in 1925, after which he worked as a sports administrator in amateur athletics. He managed the British national team at the 1928 Amsterdam Olympics and worked as a sports journalist for 40 years.

He lived in a semi-detached house at 2 Hodford Road, a typical inter-war house, wrote numerous books, was an athletics correspondent for the Sunday Times (1925-1967) and a BBC radio contributor. He has written several books on athletics and represented England and Northern Ireland in the International Amateur Athletics Federation (IAAF).

He was Honorary President of the Association of Athletic Statisticians from 1950. From 1968 to 1975 he served as President of the British Athletics Federation.

Interesting facts

Before the Olympics, he learned that he would be entered in the 100m and 200m, the 4x100m relay and the long jump. Therefore, a letter he signed as a “famous international athlete” was sent to the Daily Express, pointing out that the same athlete cannot possibly participate in the long jump and the 200m race, which start on the same day at 14.30. The letter achieved its goal: he did not have to compete in the long jump.

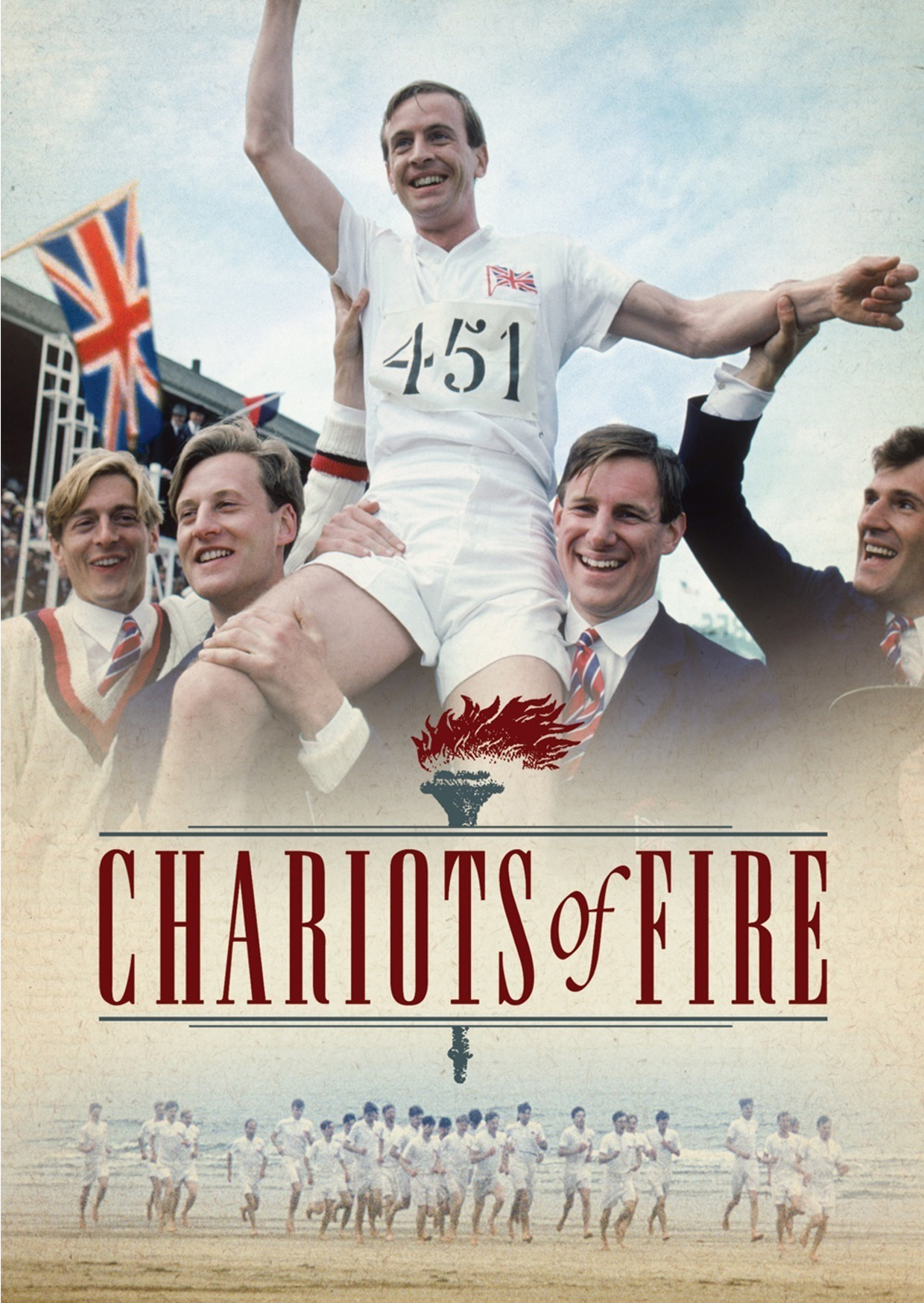

Chariots of Fire

The film Chariots of Fire (1981) made Harold Abrahams’ name known around the world. The film is a memoir of a noble race with fellow athlete Eric Lidell of Scotland, of will and perseverance and of an incredible Olympic performance.

Liddell, who held the world’s best 100-yard time, announced before the Olympics that he would not change his weekly schedule on Sunday, his day of rest and relaxation with the Lord, even for the Olympics, and would not compete in the 100 metres race. Some say that the King of England himself tried to persuade him to compete “for the glory of his country”, but Liddell replied: “God’s command comes before the glory of the country. I will not run on Sundays.” Liddell was re-registered to the 400 metres, where he won a gold medal for his country. “I ran as fast as I could in the first 200 metres and then, thanks to God’s help, I was even stronger in the second 200,” he told The Guardian.

Eventually, the Abrahams-Liddell duel did occur at the Olympics. In the 200m flat they both reached the final, but neither managed to win a gold medal. Liddell finished third, while Abrahams came in sixth.

Origins

In the second half of the 19th century, young Lithuanians, growing up mainly in the countryside, were already attending the universities of St Petersburg and Moscow, rather than Warsaw, as a kind of de-Polonisation effect. However, the national movement against forced Russification was already aimed at creating a nation-state speaking its own language.

Although the Cyrillic alphabet was replaced by the Latin alphabet, and an increasing number of books and publications in Lithuanian were published, which contributed greatly to the strengthening of Lithuanian national consciousness, the process was interrupted by the great famine of 1867-68, which led to the beginning of emigration. The target countries were mainly the U.S. and the Anglo-Saxon countries. Between 1868 and 1914, 20% of the population left their country.

Of Harold’s two brothers, Adolphe was one of the founders of British sports medicine and Sidney was a long jumper who was a member of the British team at the 1908 and 1912 Olympics.

Early sporting activities

He was probably inspired by his much older brothers to start sporting at a very early age. At the age of eight, he was already competing in races and at the age of 12, he won the 100 metres by completing the race in 14 seconds. He has suffered from a lifelong inferiority complex because of his origins. Some believe that this was the source of his endurance and his invincible will to win.

Although he had already competed at the 1920 Antwerp Olympics, he failed to qualify for the finals in either the long jump or running. After a disappointing sixth place in the 4x100m relay, the British team decided to concentrate on the sprint numbers.

To prepare for the 1924 Olympics, he hired Sam Mussabini as his personal trainer. He became the first amateur athlete to pay his coach for professional advice and coaching. His brother Sidney also helped him prepare.

In preparation for the Olympics, he broke two records on the same day. His long jump result of 7,37 metres was not broken for 32 years. And his 9.6 seconds result in the 100 yards was not certified only because of the slight downhill. However, at the 1924 Amateur Athletics Federation Championships – then the equivalent of the World Championships – he won the 100 metres by completing the race in 9.9 seconds.

But in the meantime, he had a new opponent to contend with. Scotland’s Eric Liddell finished the 100 yards in 9.7 seconds, which was better than Abrahams’ best. This may also have played a role in hiring a personal trainer, with whom he mainly honed his start and style in preparation for the short distance.

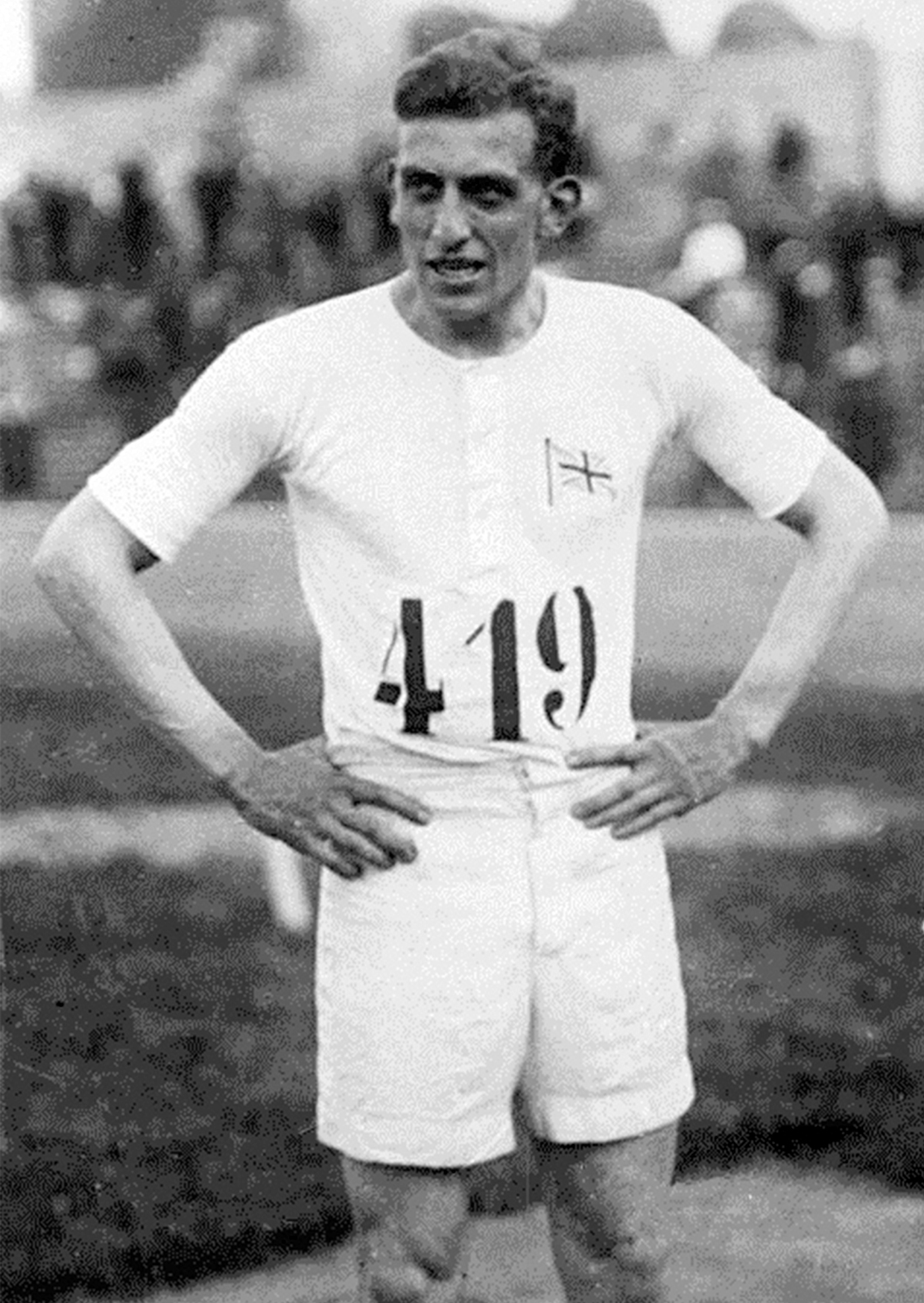

The Paris Olympics

The most memorable of the 1924 Paris Olympics was the 100 metres flat race. In the qualification stage, Abrahams broke the Olympic record with 10.6 seconds, and in the semi-finals he achieved the same time. Abraham qualified for the final from the first place, finishing again in 10.6 seconds.

“I got stuck at the start in the semi-final, but I still managed to win,” he said in a 1956 interview. A lot of people thought it was my best performance ever and asked, “What would have happened if you hadn’t stuck at the start? Couldn’t you have achieved a better time?” My answer is no, because I have done something I would never have been able to do if I hadn’t fallen behind at the beginning.”

In the final, he competed against two great American runners, Jackson Scholz and Charles Paddock (winner of the previous Olympics and World Champion) and won the race. Incredibly, Abraham set three Olympic record-breaking performances in 26 hours and became the first European and the first Briton to win an Olympic gold medal in the 100m flat.

Abrahams also won a silver medal as the first runner of the 4 x 100 m relay.

The film that made Abraham famous, Chariots of Fire, portrays Harold as an outsider at the 1924 Olympics, ostracised for his religion, even though Abraham was never a practising Jew. Norris McWhirter, Abraham’s colleague and friend, wrote of his achievement that “by sheer force of personality and with very few allies, he managed to take athletics from a minor to a major national sport”.

1899.12.15 – 1978.1.14