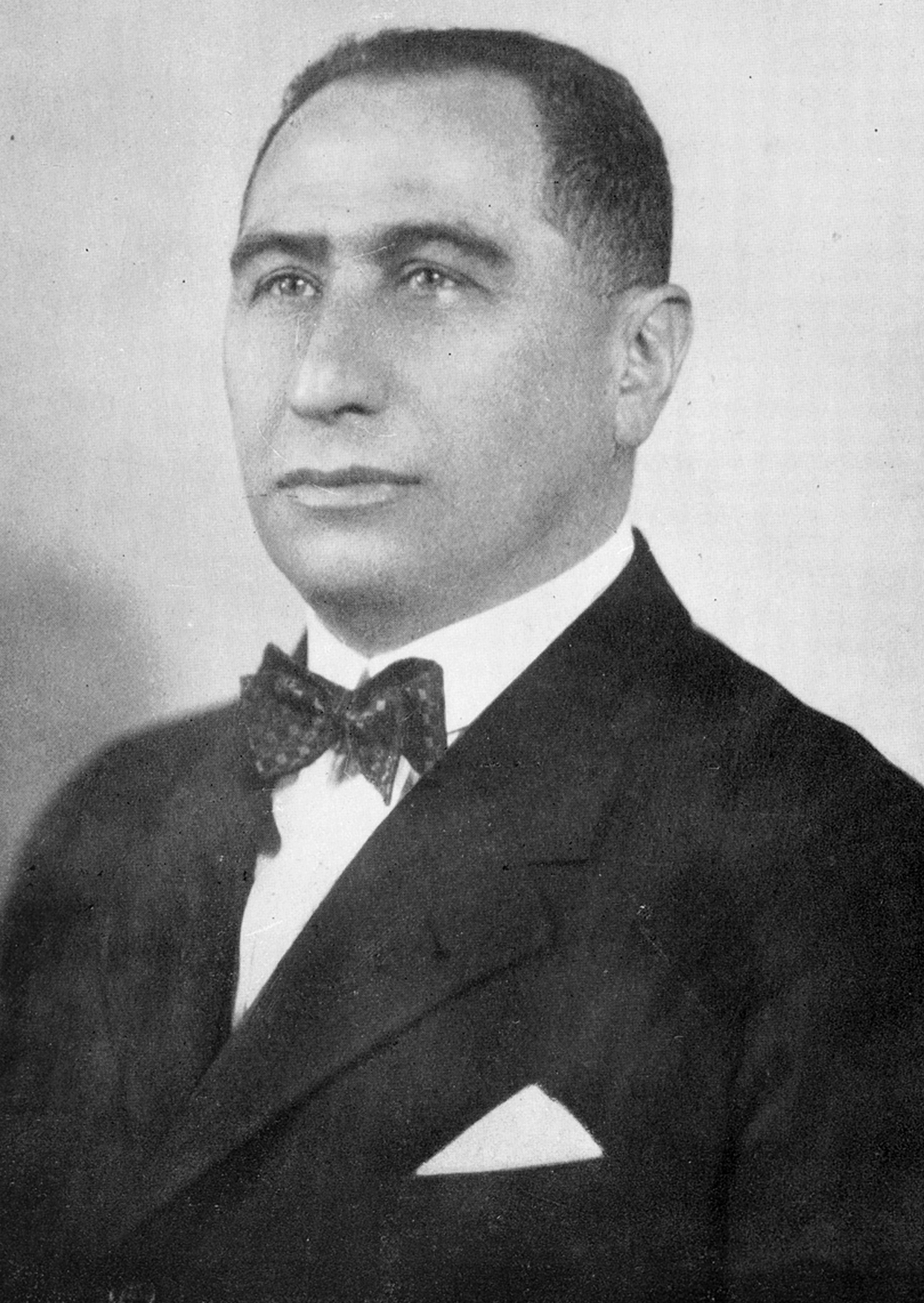

1872

He was born on 27 January in Assakürt (in present-day Slovakia, known today as Nové Sady) as the second child in a Jewish family of nine children. The large family needed support, so after four years of elementary and four years of grammar school, he started working to help his parents.

1892

He joined the Béla Egger and Tsa Company in Újpest as a commercial employee. (Also working here was the young man who later became the father of the Porsche brand: Ferdinand Porsche). The bright young man, who spoke four languages, was appointed the factory’s representative in Russia, and by 1904 he was the factory’s deputy director.

1906

The successor to the previous company, Egyesült Izzó, was founded. As a result of his diversified and outstanding work, the factory almost flourished despite the negative effects of World War I, which was mainly due to talented management. Aschner encouraged research within the company. He even donated a significant amount of money to the Minister of Culture, Bálint Hóman, to help talented students. He was already a general manager at the time, therefore, he was able to set up an endowment for the Department of Nuclear Physics at the Budapest University of Technology and Economics (also known as “Műegyetem”) in the amount of 300.000 Hungarian pengős.

1931

In this year, 95% of the world’s filament lamps were produced by five companies: General Electric ( USA), Philips (The Netherlands), Osram of Germany, Compagnie des Lampes (France) and Tungsram ( Hungary). He became vice-president and then president of the cartel they later formed. His recognition and influence at home is shown by the fact that he was vice-president of the National Association of Industrialists and a member of the supervisory board of the Hungarian Commercial Bank of Pest.

1944

He was arrested on 19 March, the day after the German invasion, and deported to Mauthausen in May. Adolf Eichmann moved into his villa. His fellow prisoners described him as the most human of men. Aschner, who was old and sickly by then, could have asked to be excused from physical work, but he worked every day with his fellow inmates. In 1944, the international partners and the management of the domestic company secretly negotiated with the SS to free him. He was finally released in exchange for 100,000 Swiss francs, and transported first to Vienna, then to Geneva.

1945

At the end of World War II, the Soviets stole most of the machines and lamps from the factory in Újpest. (It wasn’t part of reparations, therefore they took almost everything illegally.) In order to help after the huge amount of damage, he appealed directly to Rákosi to allow him to return home. Aschner returned to his company as Vice President and tried his best to get the company back on its feet. In addition to reorganising production, he also introduced the production of neon tubes.

1952

In the words of Zoltán Bay: “the old man with shaking hands, limping, and deaf” succumbed to disease. Completely robbed of his fortune, he died at the age of eighty. His death was not reported, not even in the factory’s own newspaper.

Aschner and Judaism

Aschner did not forget his temple either, as he was giving them 5000 Hungarian pengős a year. He also provided special support to the Jewish communities of Buda and Újpest. Special attention has been dedicated to supporting the operation of retirement homes and orphanages. It was a sign of his modesty that when he handed over funds to support these institutions, he explicitly asked to remain anonymous.

He could have escaped the Jewish laws, as he had a valid ship ticket to New York for the World’s Fair, but he stayed at home and worked without pay. Act IV of 1939 capped the number of people of Jewish origin that may be employed in industrial and commercial companies at 12 percent. Aschner, in order not to have to lay off his workers, advertised jobs for Christian workers, so that he could keep his Jewish workers while observing the proportion restrictions.

Aschner’s Family

He and his wife, Jolán Czettel, lived 51 years in a harmonious marriage and, according to their letters, in great love. But his wife, ten years his junior, survived him by only a few months. They had two sons. Endre died a premature death at the age of 12, while Pál, born in 1908, survived the period of great peril and helped his father even after 1945. He emigrated to Canada in 1956, and died there in 1998.

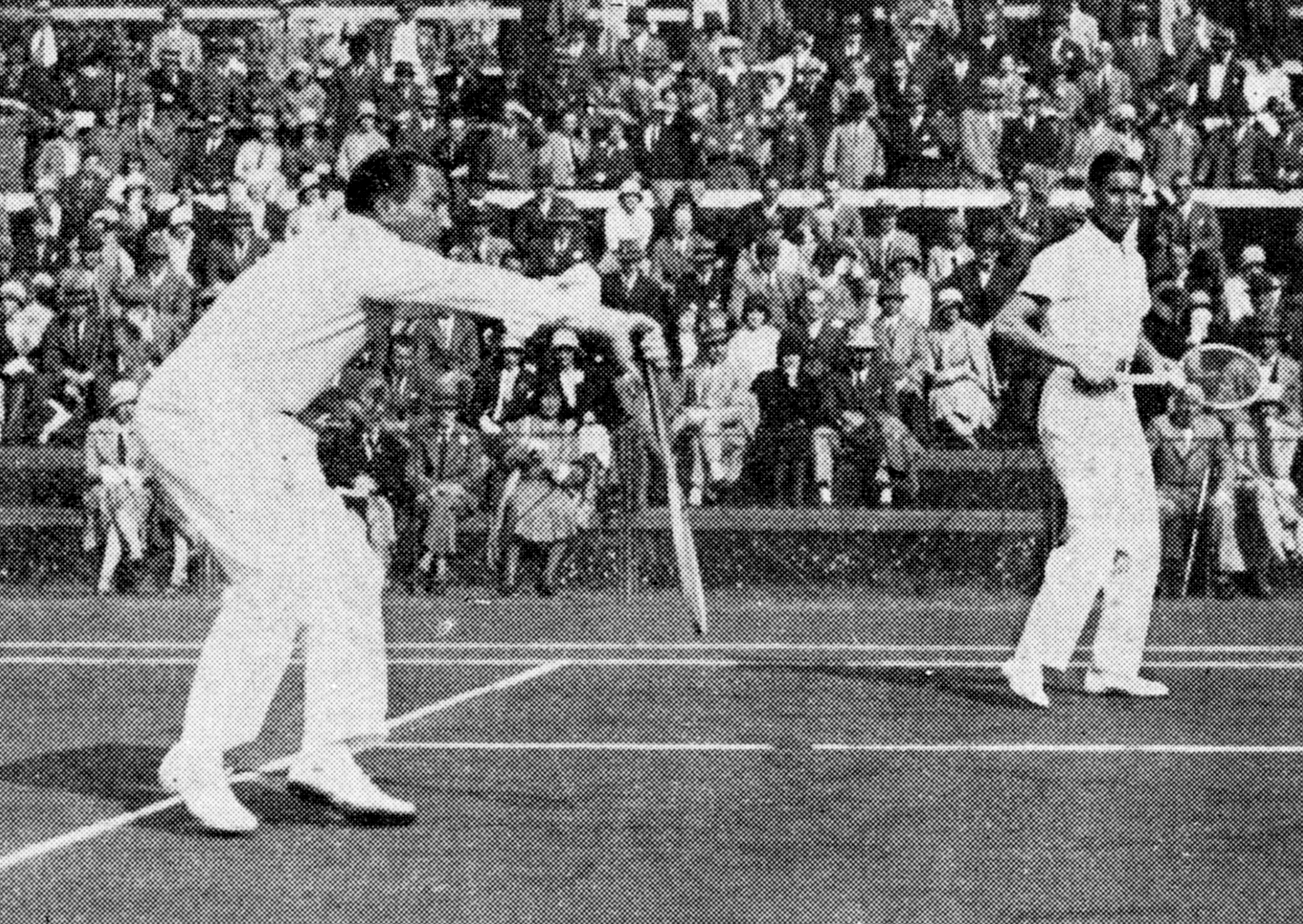

Pál Aschner was an excellent tennis player; he also played on the Davis Cup team. He was a star of the UTE “hockey team” and a certified football referee.

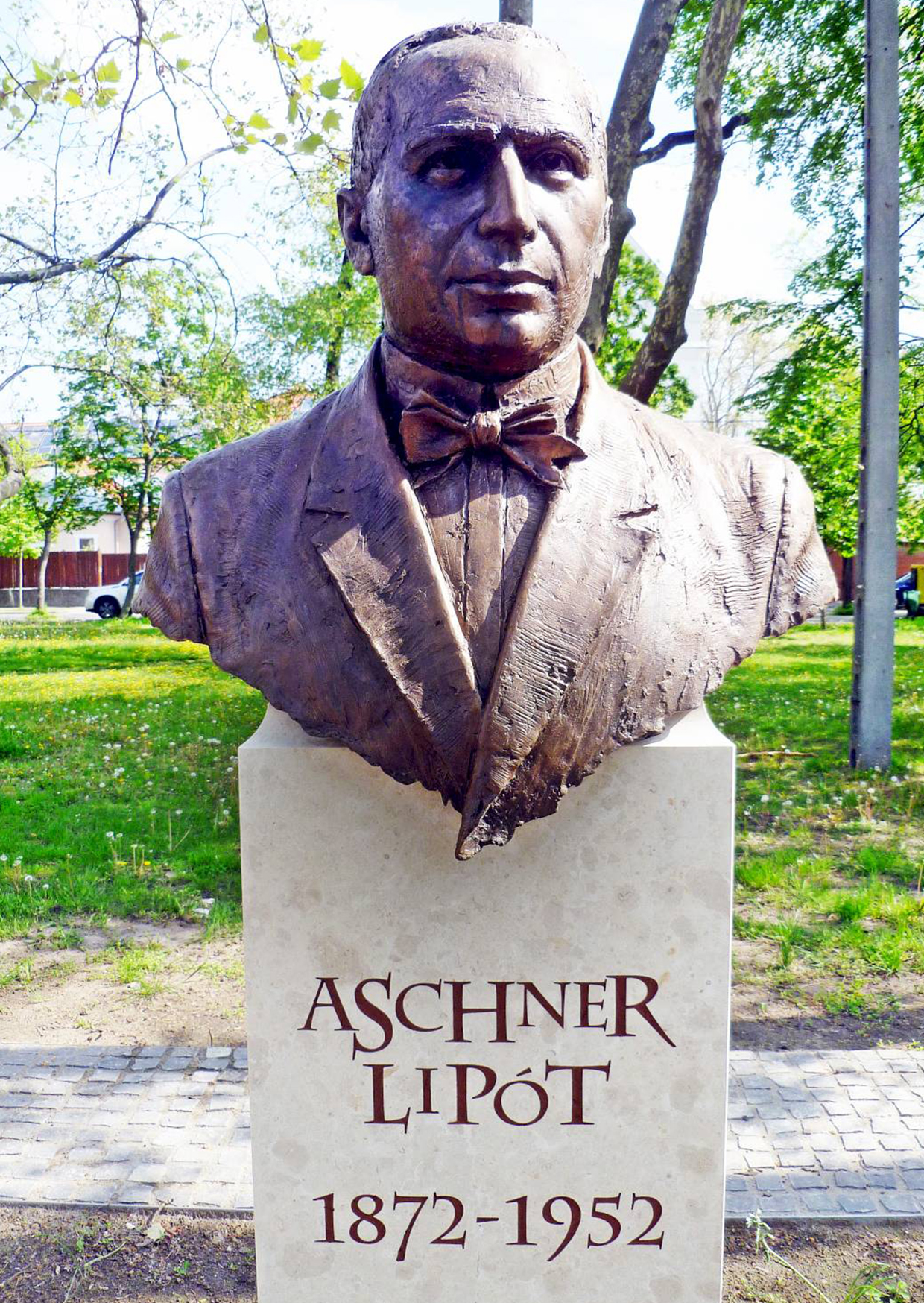

Legacy

Lipót Aschner is commemorated in Újpest with a square and a bust, a plaque on the factory wall and a relief in the stadium.

In 1989, the National Association of Industrialists established the Lipót Aschner Foundation, which founded the Lipót Aschner Award.

On the 150th anniversary of his birth, on th 27th of January 2022, his bust was erected in Aschner Lipót Square.

The book “A Man Ahead of his Time – The Life of Lipót Aschner” (Hungarian: Aki a korát megelőzte – Aschner Lipót élete”) was published by Kossuth Könyvkiadó (with the support of the municipality of Újpest).

His villa in Buda, located at Apostol utca 13, still stands today. The original tower of the building, which was unfortunately inadequately restored, was lost in the World War; moreover, its beautiful garden has been built on and replaced by a car park.

Aschner and Money

Although he disposed of a huge fortune, he lived modestly. The house at 13-15 Apostol Street was his only property. He got up at seven in the morning, took a swim, and was at the factory until half past three. He then played tennis in Újpest on one of the courts of the sports complex he founded.

Work related to sports

As a sportsman and sports manager, Aschner was involved in Újpest’s sporting life from the 1890s; he was a great lover of tennis and a regular player at the tennis courts of UTE on Népsziget from 1903.

Club management was not foreign to him either, as he founded the Ampere (later Tungsram) Sports Club in 1911 for the workers of the factory. He had been the secretary of the Újpest Gymnastics Club since 1895, but his first serious role came in relation to the construction of the football stadium. From 1921, he was co-president of the Újpest Gymnastics Association, becoming its full-time president in 1925. Today, it is the third oldest continuously operating sports association in Hungary. He served as the president thereof until 1934.

The first soccer field in Hungary, called STADION, was built in 1922 by Aschner in Újpest, together with the Mauthner and Wolfner families, also from Újpest, based on the plans of Alfréd Hajós. A total of 20, 000 people could buy tickets for the sports facility with a capacity of 200 boxes and 2,000 seats.

He had ten tennis courts built around the factory’s community centre, right next to the factory, where he himself visited almost every day. An indoor tennis hall was also built in the community centre.

In 1925, a cycling track was built around the grass pitch where the lower rows of seats in the stadium stands used to be, and from 1928, throwing and jumping fields were built for athletes. The land for further development was provided by Tungsram. UTE’s facilities were also available for use by the club’s athletes and factory workers.

The fencing hall was located at the company’s headquarters in Eötvös Street in Budapest, while the athletes of the other divisions trained in Újpest. The factory’s aquatic sports complex (later Tungsram Strand) was built on the Trianon dam, an island-like protrusion into the Danube. He also set up a rowing club on the bank of the Danube in Újpest.

In 1930, on the opposite bank of the Danube – in today’s Pünkösdfürdő Strand – the spa and sports complex was built, which was also designed by Alfréd Hajós. Of the three swimming pools, the first (50×20 m, suitable for international competitions) was used by the public during the day, while in the evenings, UTE swimmers and water polo players would train tjhere by the light of underwater reflectors.

The footballers were particularly successful. Five players from Újpest played on the 1938 national team. Between 1920 and 1942, they won five championships (1929-30, 1930-31, 1932-33, 1934-35, 1938-39) and achieved twenty league ranks.

UTE enjoyed its heyday under Aschner. It has produced Olympic champions in several sports (water polo, fencing, wrestling), with a total of seven UTE athletes standing on the podium at the games in Los Angeles and Berlin. He was no longer president of UTE when he accepted the presidency of the Hungarian National Football League.

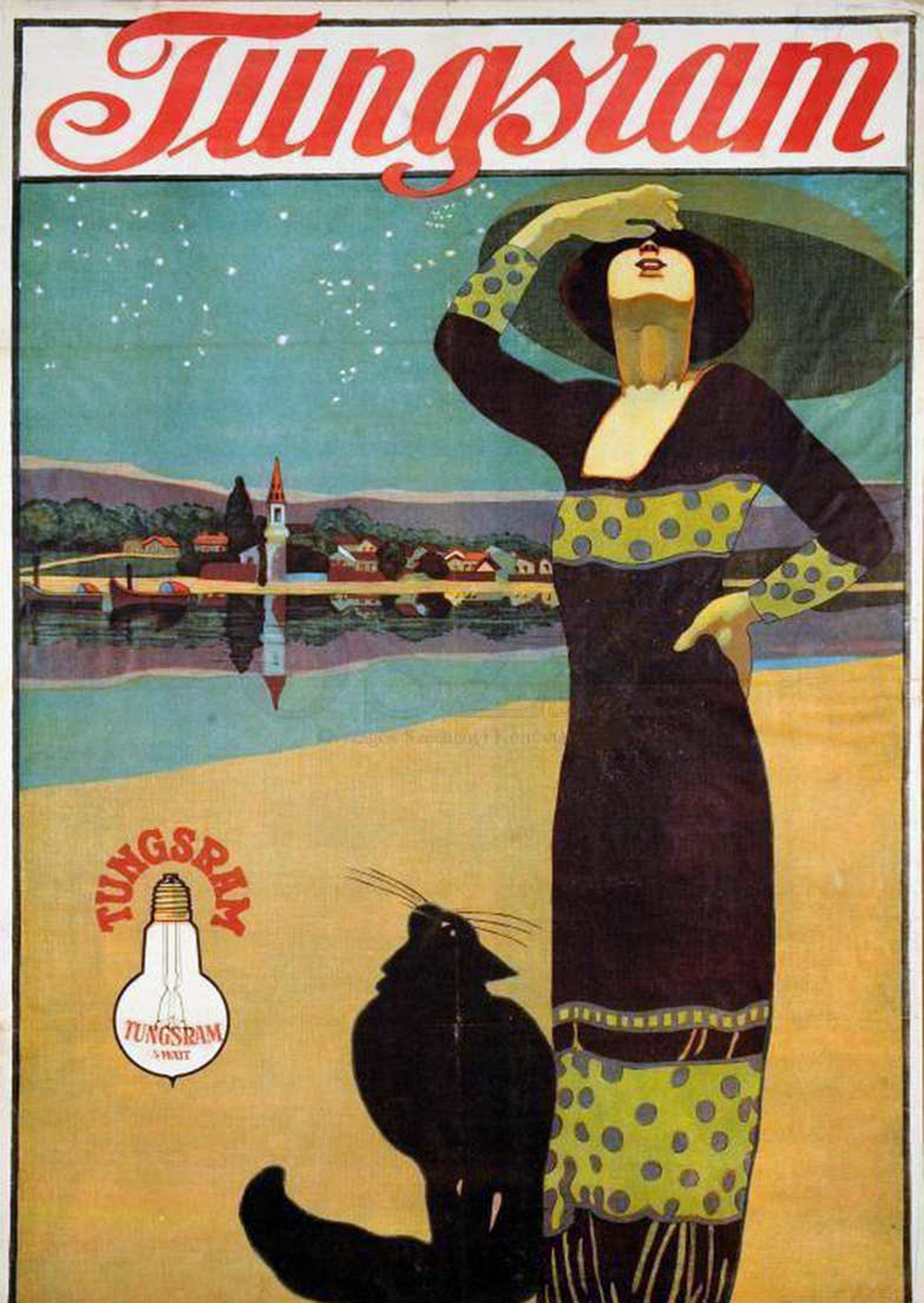

TUNGSRAM

In 1911, the factory produced the first gas-filled tungsten filament lamp. A year later, the Western Electric company of the USA joined the venture, and from then on the name Tungsram was used. The brand name “Tungsram” was invented by Lipót Aschner. From the English and German names for tungsten (Wolfram and Tungsten) and using the first German syllable and the second English syllable, the word “Tungs-ram” was created and officially registered on the 28th of April 1909. In 1932, General Electric, also an American company, acquired a majority stake in the company. (In 2022, Tungsram found itself in a difficult position to sort out its finances, and filed for bankruptcy in May, while closing some of its factories.)

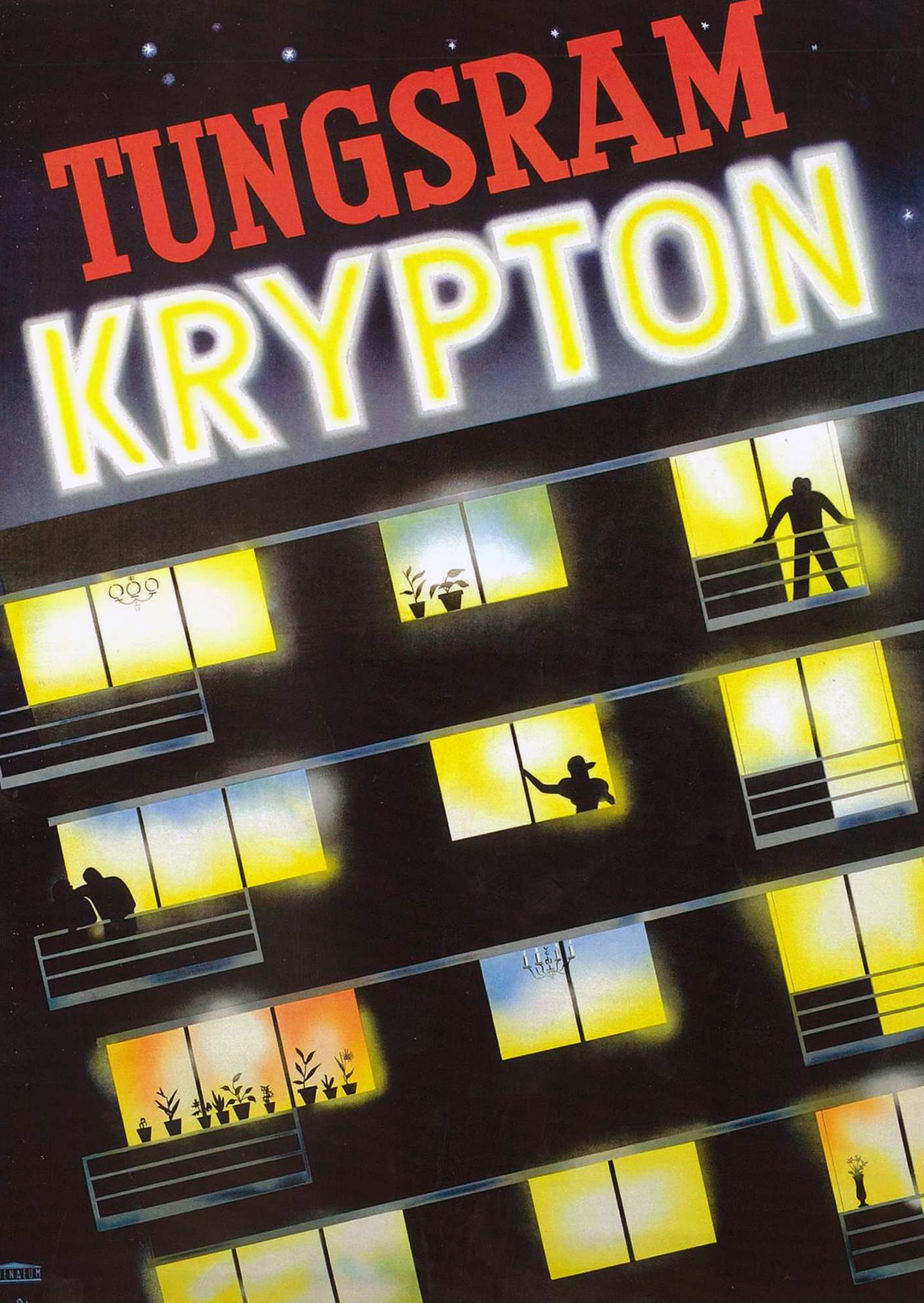

The Krypton bulb

Egyesült Izzó (English: United Bulb) established its research laboratory in 1922. Employed here was, among others, the physicist Imre Bródy, whose basic research led to the filling of the lamp with krypton in 1931, which revolutionised the production of filament lamps. By 1936, the krypton bulb had gained worldwide recognition for its longer lifespan and more economical use of light. Over the next decade, the filing of a number of important patents here helped the spread of electron tubes manufactured from the late 1920s onwards. The research laboratory’s achievements include the development of xerox duplication technology, as well as the ancestor of television, the locator technology. It was here that the company experimented with the production of radio and television picture tubes. From 1925, the company also produced radios under the Tungsram brand. Dénes Gábor (Günszberg), who later won the Nobel Prize, worked on gas discharge.

By 1939, the factory in Újpest was producing more than 25 million filament lamps per year, and with exports worth 17 million Hungarian pengős, it overtook the then-market leader, Philips.

On the 6th of February 1946, the factory was the scene of a world premiere. It was here that physicist Zoltán Bay, head of the research laboratory, successfully carried out an experiment in which he picked up radar echoes from the Moon with a locator produced in the laboratory. (Zoltán Bay received the Yad VaShem Award for saving 13 Jewish engineers.)

Tungsten, the raw material for Tungsram bulbs, was supplied by the Belgians from a deposit in the Congo. After 1945, Belgium stated that if Tungsram Rt. were nationalised, no raw materials would be supplied. Thus, it was the only company to operate as an Rt. (English: joint-stock company) during the Rákosi and Kádár era in Hungary. To clarify matters and for the sake of accuracy, the Hungarian National Bank was also a joint-stock company.

1872.1.27 – 1952.1.18